Recent Press

The BrEaST Show Video Exhibit Shown at NINE Gallery

Inside Blue Sky Center for the Photographic Arts, Portland, Oregon, July 2023. This exhibit was curated by Bonnie Laigne-Malcomson, (retired) Harold and Arlene Schnitzer Curator of Northwest Art, Portland Art Musuem.

Interview at the Hoffman

Laura Ross-Paul “Life for Breasts” Artist Talk

Manzanita, Oregon July 2019

This video playlist contains all 5 parts of the artist talk: Intro, Pre-Breast Cancer, Going Through Treatment, Processing My Journey, and Q and A.

Willamette Weekly

2014

Urban Forest

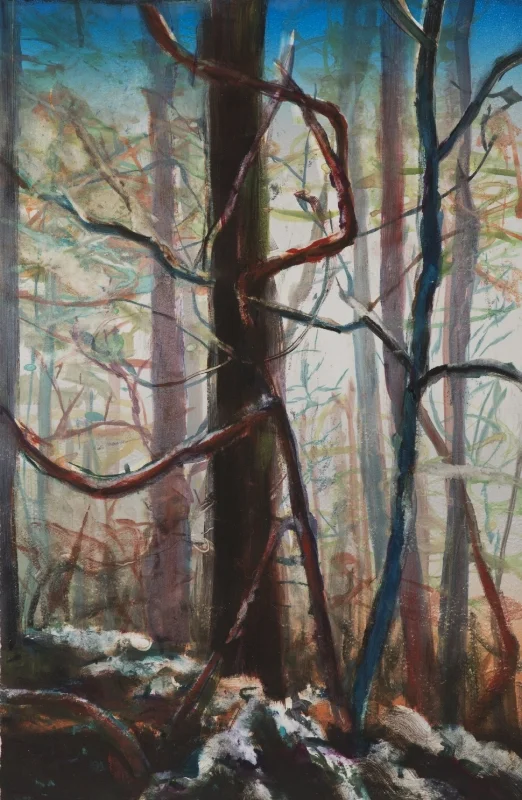

Laura Ross-Paul is known for her evocative paintings of the human figure, but many of the paintings in Urban Forest have no people in them at all, only trees. Ah, but not “only” trees—these are roots and trunks and limbs rendered with an almost supernatural reverence. The looping, arcing contours recall previous series in which Ross-Paul depicted twin brothers linked by curved tree branches and auras of mysterious energy. This is an artist with a profound transcendentalist relationship to the natural world.

—Richard Speer

Willamette Weekly

2012

Connect

The light of cellphone screens and laptops illuminating their users’ faces in dark rooms provides inspiration for Laura Ross-Paul’s new body of work, Connect. The paintings depict young people staring at screens even in the midst of ostensibly more interesting activities such as fireworks displays, picnics and star-gazing parties. But Ross-Paul resists the temptation to wag fingers at the perpetually logged-on young'uns, instead depicting the screens' light with the same mystical reverence seen in Renaissance paintings of candles, halos and stained-glass windows.

—Richard Speer

Visual Art Source

2010

Seasons

Figurative painter Laura Ross-Paul combines a free, neo-impressionist technique, an interest in Jungian symbols and archetypes, and a transcendentalist’s love of nature. These elements integrate seamlessly in “Seasons,” as her current exhibition is titled. With loose, but never sloppy brushstrokes in oil paints and encaustic medium, she lends to her figures a John Singer Sargent-like sense of aristocracy and idealization. Most often her subjects are young and they are adorned in contemporary garments. Sometimes she depicts them nude or semi-nude, allowing them to speak of timelessness rather than Zeitgeist. Ross-Paul is inspired by the Oregon coastline, yet her depictions of frolicking beachcombers and surfers, as in “Wave” and “Soup,” sometimes cross the line between the halcyon and the sentimental.

It is in her other major body of work — her forest fantasias — that the painter’s most affecting gifts come to the fore. Her pictorial and poetic sensibilities are activated by dappled light, tangled undergrowth, and the interplay between fir and deciduous trees. While her ocean idylls reveal all contours in flat, midday sunlight, her forest paintings withhold their potentialities. Embraced in verdant habitats, teenage models, who might in lesser hands come across as displaced mall rats, take on allusive overtones. The skateboarder becomes a forest sprite; the girl in fifth-period algebra transforms into a water nymph.

In “Early Spring” a shirtless boy wields a large branch that is curved like a scythe, its contours alternately following and bisecting the lines of the blossoming tree behind him. He is, we sense, more than a boy holding a stick. Regarding the viewer implacably, his expression too cagey to be serene but too beatific to be sinister, he challenges us to divine his identity, his narrative, and the implications of his prop.

Another of this veteran painter’s talents is the invention with which she communicates a mystical reverence for nature through her handling of background atmospherics. The fiery aurora borealis in “Celebration,” the shimmerings of water and sky in “Fall River,” the swirling dance of snow flurries in “Scarf” and “A Light Dusting,” and the opulent textures and pastel hues of the flower petals in “Early Spring” all create dizzying backdrops that, rather than distracting from the foregrounds, impart a pulsating, magical quality, heightening compositional and thematic drama. She has written that she titled the show “Seasons” because she wanted to evoke those imprecise moments when something changes in the air and one senses that the season that has been is giving way to the season that is to be. It is a phenomenon well-suited to the generous sfumato of her technique. A longtime associate professor of painting at Portland State University and later Lewis & Clark College, Ross-Paul recently retired from teaching, renovated her studio, and plunged into painting full-time. The current work is her most vital in years, invigorated by dueling impulses to portray dark mysteries and illuminate metaphysical truths.

—Richard Speer

art ltd.

2009

Artist Profile

Laura Ross-Paul paints: “the wonderment of our interconnection with nature and with each other, the web of life.” Based in Portland, Oregon, she spends much time in a raw family cabin and her adjacent yurt studio in a beach town close to an old-growth forest. Amid ancient trees and sea, Ross-Paul is continually amazed how nature and human life share patterns, each fitting in and supporting the other. Her art depicts these “patterns and moods in natural settings that echo patterns and moods found in human life.” Thus, her thoughtful art reveals how nature and humans continually play off each other, both compositionally and psychologically. The mood of the sky or the bend of a cloud mimics the bend of a human back as nature takes on the posture of the other. “A splayed hand echoes a leaf; a branch goes down a stream, intent on passing some rocks to continue its journey.” To achieve synchronicity, Ross-Paul spends a great deal of time capturing natural details and working on precise body language and facial expressions. She “sweats bullets” getting the correct body language, the exact emotion and facial expression. In one painting, Archway (2009), two boys hold ends of a flexible stick that forms a loop. In the background, a tree made out of two interconnecting trees symbolically represents the actions and relationships of the two protagonists in the foreground. The stick represents their being two within a single relationship. Working with duality in nature, humans, human pairs, and twins, Ross-Paul finds that dissimilar aspects of self forever try to become one with the whole, struggling for change and balance, but always through “wonderment.”

Through much trial and error, working with the Portland-based Gamblin Artists Colors, Ross-Paul and Martha Gamblin arrived at a technique that is unique to Ross-Paul and gives her oil paintings the vibrant blend and luminosity of her watercolors on rice paper. While the oil paint is still wet, laying flat on the floor, she pours a mixture of Galkyd resin and cold wax. The wax chemically melts into the resin. To assist the process, Ross-Paul rolls the canvas back and forth, sometimes even pounds it. The resin and wax pick up the wet paint and carry the pigment in a suspended state in a way that a brush cannot. When dry, the painting appears incredibly ephemeral. At this point, the artist hangs it again and “adds more painterly, muscular marks, which counter the ephemeral,” giving her art its distinct balance of energy, delicateness, floating, melting, and radiating light.

An aspect of Ross-Paul’s life that deeply affects her work was “being the first woman in America to volunteer and receive a cryolumpectomy,” successfully overcoming breast cancer at Detroit’s Karmanos Cancer Center. Now cleared for many years, it has shifted her focus to a cosmic, shamanistic view of life. Her 2003 painting, Juggle #3, on view at her recent solo show at JoAnne Artman in Laguna Beach, depicts a woman running with zest and vigor, as she balances three balls on top of each other. Their colors are orange-red, blue and white. The blue and the orange-red could represent the healthy and unhealthy breast (they are breast size) while the white could represent the “ice ball” that was used for the surgery. Interestingly, this was the last painting Ross-Paul created before finding out that she had breast cancer; and it was an “ice ball” that eventually saved her breast. Since that life-changing incident, Ross-Paul’s work has become a reverie of an altered state of consciousness. Her enigmatic dream-like imagery erodes the mundane as nature and human energy endow Ross-Paul’s art with the unexpected and magically superb.

—Roberta Carasso

art ltd.

2008

Northwestopia

The conceit of the Pacific Northwest as Edenic natural utopia (witness ubiquitous media coverage trumpeting the region as exemplar of all things green and sustainable) extends back to the Manifest Destiny and even further. But the strain of Northwest utopianism that painter Laura Ross-Paul mines in her latest solo show derives from her native Oregon’s history as a hippie haven in the 1960s and 70s. That is when Ken Kesey, Ken Babbs, and others among the Band of Merry Pranksters settled in the bucolic environs of Eugene, far away from the political and cultural hubbub of Berkeley and New York. Just down the road from Eugene is Veneta, Oregon, where Ross-Paul took her inspiration for these oil and encaustic works on canvas. The town is the site of the annual hippie bazaar known as the Oregon Country Fair, where last summer the artist snapped verité-style photographs that she later collaged, then adapted into the paintings that comprise her new show “Northwestopia.” The loose, sometimes blurred images that resulted have an Impressionistic quality that captures the dappled light of Sylvan Central Oregon at the height of summer. The show could aptly have been subtitled “Étude on a Dapple.”In works such as Chumbleighland, the artist uses asymmetrical composition to highlight a trio of enigmatic figures: a female gazing into the distance, an angelic waif with downcast eyes, and a white-haired man whose face is turned away from the viewer. It is hard not to see the grouping as allegorical, although Ross-Paul wisely leaves the allegory unstructured and unexplained. In Garland, a figure wearing a Renaissance-style headdress speaks to the romanticism of an earlier time. Second Creek, Pipes, and Junction play off the motif of figures standing close together but looking in opposite directions: one to the ground, the other to the sky; one to the left, the other to the right. Throughout, horizontal swaths of impasto are punctuated by dark vertical trees. The figures’ garments pick up the colors of trees and sky, positing a transcendentalist melding of human being and nature. The painting Coast, with its flat lighting and beach scene, does not come from the Country Fair collages, lacks that series’ mystical atmospherics, and does not particularly cohere with the rest of the show.

—Richard Speer

Exhibition Catalog

2006

Naked

The psyche, the soul, the essence of the individual and how that individual fights for, negotiates, or embraces the precariousness of existence has long been the subject of painter Laura Ross-Paul’s art. In all of her work, the drama of existence takes place in nature. There are no women at the window looking out, no mothers and children reading in the parlor. Men and women dance, embrace, and struggle outdoors. Cocky urban adolescents pose and strut in front of cloudy baroque skies. Women climb trees, balance on limbs, and then let go. In Ross-Paul’s newest works, the dramas of life still play out in nature, but much has changed. Previously, when the artist placed her figures in the dappled forest light they ran or danced, but here women walk quietly. At the beach, they struggled against or reveled in the immense force of the ocean’s waves. The protagonists in these new paintings and watercolors are contemplative rather than active; intensely quiet rather than intensely emotional. They are, it appears, in a state of suspended animation. They are thinking. They are also naked.

Laura Ross-Paul has been painting the human figure in nature for more than twenty-five years, and rarely has she chosen to paint her figures nude. Men walk on the beach stripped to the waist, and shirtless teenage boys show up in pants sagging below the hip. Girls wear sports bras and athletic shorts to the shore, and women wear simple dresses to negotiate waterfalls. In earlier works such as Beating Back the Icebergs, 1987, when a figure appears to be naked, water hides much of the body. Those paintings are more about the capacity of gesture to form metaphors for the human condition than they are about the bodies of the protagonists. Ross-Paul’s 2006 exhibition “Naked,” at Froelick Gallery in Portland, Oregon, is both an extension of and a departure from that approach.

During conversations over the past few months, Ross-Paul explained that the impetus for these new works was her experience of personal physical vulnerability as she was diagnosed and underwent cryolumpectomy, an experimental treatment for breast cancer. As she has been examined, operated on, re-examined and studied by doctors, residents, and medical students for three years, she has been quite literally naked. That feeling of exposure has been compounded by the artist’s decision to speak and write about her experiences in order to publicize this new treatment.

There are two obvious ways to be naked — alone and with others present — and Ross-Paul is exploring both possibilities in her new paintings. It is also possible to be naked and unknown, or naked and known; and the paintings address these more complex ideas as well.

In the oil paintings Dapple and Filter, the artist places a woman, arms crossed to cover her breasts, on a trail in the woods. As the light filters through the trees, it fractures into colors that play across her body, making it difficult to see her features or guess at her emotions. In a third painting, Curve, a recumbent nude also remains a mystery. Her back is to us and she is looking upward to observe a phenomenon of lights that forms a huge semi-circle in the sky. The anonymity of these figures is reminiscent of earlier works. In the 1986 painting Splash, for example, facial expressions and anatomical details are not important. The playful, exuberant gestures, not the identity of the two individuals splashing each other, are the subject of the painting. In Filter, Dapple, and Curve the relative anonymity of the figures also conveys universality, but the mood is different. Action is subdued and it is the ethereal play of light, not the tactile forces of water, that engulfs these women.

Another painting with a single female figure, Buoy, takes a different approach. The woman, who is standing in the ocean with her back to the horizon, is fully identifiable. We can easily see that she is young, blonde and naked, with full breasts and hips. Again she crosses her arms to cover her breasts, but her left nipple is visible. She is not fragmented by light, nor does the sea engulf her. She looks us straight in the eye, yet we still do not know her.

This same woman appears in the painting Drop. Here she is also naked but is now surrounded by others in one of those casual gatherings common to the Oregon beaches that Ross-Paul frequents with her family. In this painting, young people gather in the foreground taking a break from their activities in the surf. They pay little attention to the naked woman in their midst, and she pays little attention to them. Some experience has separated her from the lives of those around her. She may be exposed, but they do not see her. She makes eye contact with the viewer, but her steady gaze does not create a bond and instead establishes her distance. She is very much alone.

There is a symbolic difference between water and light. Water can be an element that transforms through baptism, or a force that threatens life itself. Light can be symbolic of revelation, transcendence, or ecstasy, or it can blind one to the self or the world. Many of the artist’s paintings from the last two decades have invited these readings. However, in these new oil paintings, Ross-Paul’s figures are neither engulfed nor ecstatic. Something has changed them, estranged them from their previous understanding of themselves, and from the lives of those around them. Whatever it is, it is something they do not yet comprehend.

Watercolors

If the figures in the oil paintings represent the difficulty of understanding many of the essential experiences that make up a life, a series of new watercolors is the result of a search for that understanding. They are graceful and intuitive expressions of the artist’s interest in connections between the body and the spirit.

In this body of work, Ross-Paul is exploring the insights and symbolism of other religions and their parallels in her own Christian beliefs. Each of the new watercolors springs from one of the seven Buddhist chakras. Chakras are traditionally associated not only with areas of human body but also with colors in the spectrum. The artist has included that color symbolism in these works.

This is not the first time Ross-Paul has chosen to base an artwork on a single color or used color as part of the symbolic or metaphoric system for a series of work. For example, Beating Back the Icebergs uses a deep, cold, green to convey isolation and futility. It is the brilliant yellow of the sun-soaked water in Splash that evokes the joy of the couple. In a series of screen prints about the five senses created in 1993, the artist chose to pair each sense with a color — red with sound, green with touch, blue with sight, and so on. The sixth and final print in the series, representing a combination of the senses, was paired with a metallic copper.

Like the oil paintings, each of the new watercolors includes a nude young woman. Sometimes she is alone, but most often we find her in the company of a spiritual alter ego. In four of the new watercolors the artist has paired two young women — one clothed, one naked. In Red, the color associated with the chakra located at the base of the spine, the two women sit side by side on a white cloth. The naked woman sits in the lotus position with her eyes closed. Starting at the crown of her head and descending downward, her skin has been adorned with a seven sets of white concentric circles. In conversation the artist has suggested that these circles can be read as corresponding to the seven Hindi chakras, the Christian sacraments, and to various glands and organs of the human body. In contrast, the second young woman wears a black leotard, her eyes are open, and, although she sits with her legs crossed, on her the position looks casual and secular. We sense that she is not quite aware of her companion, her sacred self.

In one of the most powerful images in the series, Orange, the two woman are facing each other. One is crawling forward, while the other leans toward her. Unlike the figures in most of Ross-Paul’s current work, both women are naked and look at each other rather than at the viewer. The color orange is associated with the sacral chakra, which represents sexual energy, and this watercolor appears to be about emerging sexuality. Ross-Paul has drawn an outline of a tiger, like a spirit, over the back the crawling figure. In another work, Violet, Ross-Paul has placed a young woman lying prone on a white cloth. In this watercolor, a transparent figure also hovers over her. Violet is the chakra associated with the divine and transcendence, and, in keeping with that symbolism, the figure lying head to foot with the young woman is the sleeping Buddha.

Laura Ross-Paul, as she has sought to understand her life and the forces that shape it, has always made paintings that employ symbols and metaphors. In addition to codes of color, the artist has frequently overlaid her figures and landscapes with abstract shapes and linear diagrams and created compositions that purposefully employ geometry. She has noted the circles, spheres, and squares that are part of our surroundings and studied fractals patterns and the Fibonacci number series as they relate to structures in nature. These abstractions are tools that we use to map the beauty and complexity of the world, and Ross-Paul has incorporated them into the natural and symbolic content of her work. Like her fascination with the system of chakras, these elements reflect her curiosity about underlying patterns and correspondences. What meanings we assign to the visual and mathematical underpinnings of our world are part of the discourse of religion, science, and art. In these new oil paintings and watercolors, Laura Ross-Paul continues to add her voice to that discourse.

—Terry Hopkins

Terri Hopkins is the director and curator of The Art Gym at Marylhurst University in Portland, Oregon.